Monday, December 31, 2007

Sketches: Trellick Tower

I can see this building everyday from my window at work, it's an intriguing shape from far away. So yesterday, I went very close to it and discovered this incredible abstract pattern.

Erno Goldfinger's Trellick Tower in Kensington

Many people across the country were aghast at English Heritage's proposal that a number of council estates, including examples of tower blocks, be preserved for posterity.

But not every council estate and tower block is a modern slum. In fact, well designed and well built, they have survived to continue providing relatively decent housing for working people. They have survived to symbolise a period of postwar architectural and artistic history which is only just beginning to be recognised for the advances it made.

The first postwar estates were a massive advance on the conditions, which the majority of working class people had known. Their development brought together young architects and engineers excited by the prospect of building for the needs of ordinary people. Together they faced a huge challenge. Around 4 million homes were destroyed during the war and many that survived were slums. The 1945 Labour government launched a massive housing programme, and issued new housing and town planning standards.

Many of the proposed housing schemes at this time, such as Erno Goldfinger's Trellick Tower in Kensington, were based on ideas first pioneered by the Swiss architect Le Corbusier, blocks of flats and maisonettes built on columns which also contained shops, nurseries, community centres, doctors' surgeries and, in some instances, roof gardens.

These estates were designed for a mix of people, some pioneered special facilities for pensioners or began to look towards the needs of single people. But the money for the more grandiose schemes quickly began to run out. Within three years of winning its 1945 landslide victory, Labour brought in the first austerity measures and cut back on housing standards. A period of corrupt collusion between contractors and local councils followed. One council after another was half bamboozled and half bribed into buying prefabricated tower blocks and low rise housing which no-one knew how to put together. The shoddy materials and building practices of these years resulted in the gas explosion at Ronan Point in East London in 1968, killing five people.

The original idea of prewar architects was for apartment blocks set in parkland and containing all the facilities that people and their families would need. However, the vast majority of working class estates built in the 1950s, 60s and 70s were a travesty of that idea, and even those that did strive to meet at least some of the ideals were undermined by local authority cuts in maintenance and repairs. They were also doomed by the prevailing ideas of those who designed them - reformists with a vision which resulted in some of them believing that everyone should live in Le Corbusier style tower blocks. They were prepared to compromise with the lack of resources made available to build their schemes, and sanction the construction of badly built estates.

Many tower blocks are well past their sell by date and should be knocked down, but we should not demolish them all and replace them with `conventional' houses, particularly when such houses are so small that the former tower block residents protest about being moved, as they have at Hackney's half demolished Holly Street estate. However, until we have a world where people, rather than profits, come first working class housing will remain a problematic issue.

Trellick Tower; Erno Goldfinger

| Project | Trellick Tower |

| Architect | Goldfinger, Ernö |

| City | London |

| Country | England |

| Address | Golborne Road, W10 |

| Building Type | Row house Slab, gallery access Slab, gallery-access, skip stop Tower |

| Number of Dwellings | 317 |

| Date Built | 1972 |

| Dwelling Types | 1,2,3 BR flats; 3BR maisonettes |

| No. Floors | 31 |

| Section Type | skip-stop |

| Exterior Finish Materials | concrete, wood, metal |

| Construction Type | poured concrete cross walls, pre-cast concrete |

| Ancillary Services | elderly center, nursery school playgrounds, shops, garage |

Ernö Goldfinger was a member of an important group of European émigré architects that arrived in London in the late 1930’s. His work of this period was limited to a few small commissions, the most notable of which was a group of 3 row houses on Willow Road overlooking Hampstead Heath where the architect and his wife lived until he died in 1987. Goldfinger began to receive larger commissions in the years following WWII when he began to actively promote the design of high-rise apartment buildings and his reputation rests mostly with several high-rise projects and buildings designed between 1959 and 1972. The Trellick Tower is the largest and latest of these projects, a 31-story apartment slab, part of a complex of several buildings in North Kensington called Cheltenham Estate, built for the Greater London Council. When it was built, Trellick was one of the tallest buildings in Europe and it came to epitomize all that was thought to be wrong with modern housing and urbanism following the wave of negative public sentiment about this kind of high-rise apartments that swept many countries in the 1970’s.

As Gold finger’s practice began to grow in the 1950’s he designed several small buildings that stand out as precedents to Trellick and provide links between earlier CIAM interests and Willow Road, and the tall Brutalist projects of the late 1960’s. This group of buildings includes the headquarters for the Communist Newspaper, the Daily Worker Buildings, 1946, a 5-story block of flats on Regent’s Park Road, 1954, an office building on Albemarle Street, done in 1956, and a small factory for the furniture manufacturer Hille of 1956. These are all examples of late Functionalist buildings that express an architecture of exposed concrete structure and infill panels, details, and materials. While these buildings were the result of the modest commissions available to a small office, Goldfinger also continued his interest in skyscrapers dating from a 1933 proposal done for the CIAM exhibit in Athens for the design of a 22-story, freestanding apartment block. In 1955, Goldfinger and H.T. Cadbury-Brown, designed a 28-story office block at Moorgate that was done as a way of exploring the design issues of a tall building. This project continued the preoccupation with frame and infill, but also added several new design features that would become Goldfinger trademarks: the external expression of vertical service cores, a differentiated base and top, and the hierarchical division of the façade into horizontally differentiated zones. The perspective rendering of the Moorgate project is a reference to Le Corbusier’s Algiers tower of 1938 and the early schemes for the unité d’habitation in Marseille of the late 1940’s although the façade depth is achieved through a process of erosion of the frame as compared to the additive brise soleil employed by Le Corbusier. The following year Goldfinger designed a 13-story, residential slab at Abbots Langley where access galleries were used at every third floor.

The commercial complex at Elephant and Castle, designed in 1959, although not housing, is the first completed example of the mature Goldfinger articulated frame high-rise building. This was the result of a limited architect/developer competition. The first stage included a 17-story slab, three lower 8-story slabs, and a theater arranged around a tight courtyard. The articulated frame is now expressed in both additive and subtractive modes in addition to a more developed pilotis, the banded horizontal striations, external service cores, and developed roofs, details that became Goldfinger leitmotifs. Unfortunately, the exposed frame and balconies provided an attractive roost for pigeons and Elephant and Castle was subsequently covered with wire mesh. Another similar office complex for the north end of Bedford Square was proposed two years later that included a 33-story tower to be built on axis with the square. While these projects were office complexes and a certain amount of criticism was leveled at the architect for manipulating the building exteriors in a way that suggested something other than homogenous interiors, they are clear prototypes for the two large housing projects that come at the end of Goldfinger’s career, London County Council’s Rowlett street housing, that included Balfron Tower (1963-68) that was 27-floors high, making it one of the tallest apartment buildings in Europe, and the GLC Trellick Tower, that was part of the Cheltenham estate, at 31 stories, making it the tallest public apartment building in Great Britain, finished in 1972.

Balfron and Trellick towers have much in common. Both were part of staged projects that included other types of housing, community buildings and public open spaces. Both share the concept of the articulated tower that had been developing in the Goldfinger oeuvre during the late 1950’s and 60’s and both are similarly sited and share similar architectural details and organizational ideas. On each site, a separate lower slab placed at right angles to the taller tower forms an “ell” that helps define the interior of the site. The tower is seen as a tall vertical element that dominates each site. Unlike typical zeilenbau siting, these slabs can be sited on either a north/south or an east/west alignment and, because of this, more effectively enclose the community spaces on the interior of the block and define the perimeter of each site. Balfron faces east/west while Trellick faces north/south. The sectional organization features an enclosed gallery at every 3rd floor with entrance and stairs to flats or maisonettes above and below the access level. The galleries connect to a detached vertical circulation tower with bridges at every 3rd floor. The circulation element is rendered as a separate small tower and, in addition to elevators and stairs, contains mechanical equipment, including the boiler, as well as shared community spaces. The bridge elements between slab and tower are insulated with neoprene pads to achieve sound and vibration isolation. The opposite end of the building is expressed as a vertical zone of walls and different windows reflecting the presence of the 2nd stair and a zone of different dwellings that occupy the end of the building as compared to the side. Goldfinger was critical of the shopping floors in the Marseille block. But he included a zone of maisonettes with “pulpit” balconies (a la Le Corbusier)--at mid-building in Balfron and at the two-thirds point in Trellick--that is expressed as a horizontal interruption to the vertical continuity of the south façade. The gallery facades are expressed as alternating horizontal bands of gallery windows or fully glazed dwellings. The pilotis–styled base is expressed as a higher zone of community spaces although the jardin de toit so precious to the Corbusier prototypes is conspicuously missing in the English version of the unite.

Trellick has a mix of 9 different flats and maisonettes. All dwellings are through apartments with windows on both sides of the building that are entered from the gallery with stairs connecting to the floors above or below. The kitchen and dining area are located at the gallery level of the maisonettes and open to large balconies facing south and the stair connects to the level below where rooms open to both sides of the building. Goldfinger was known for careful detailing and Trellick has many design innovations such as the sound-proofing (Goldfinger wanted double glazing to help control the noise from the trains leading into Pancreas Station), lighting, windows that pivoted for cleaning, large rooms, individual fan-coil units for heating and there were spectacular views across London. Goldfinger used proportional systems in his buildings applying a modular grid and regulating lines to achieve more harmonious results. Apparently, the added 4 floors in Trellick and the repositioning of the horizontal band of maisonettes were done to improve the overall proportions over Balfron. The rendered axonometrics that were an office trademark showcase the precise proportions of these deep, gridded facades.

Goldfinger was an advocate of hi-rise living and was committed to the Ville Radieuse concept of the tower in the park. He even wanted to replace Hampstead (where he lived) with 40-story skyscrapers to be placed around the perimeter of the park. Goldfinger and his wife lived in flat no. 130 on the 26th floor of Balfron for two months as a publicity stunt when the building was opened to promote the idea of tall buildings for social housing. He made the point that this was done to experience what he had designed and Ernö and Ursula were featured in the national press and on T.V. & radio poised on their balcony. The Goldfingers threw parties for the tenants and Ursula kept notes of the experience. And, he discovered problems from this experience, that the 2 lifts at Balfrond were not enough and that there were problems with the heating systems.

Shortly after the couple moved back to their house in Hampstead, a new concrete high-rise apartment building at Rowan Point partially collapsed after a gas explosion in the kitchen of a flat on the 18th floor. One corner of the building sheared off, several people were killed and there was a lot of damage to the building. This event was not wasted on Goldfinger who felt that the prefabricated concrete system employed in the construction of Rowan Point was too weak, that poured in place concrete was better. But the Rowan disaster, turned public opinion against high-rise apartments in general and, coming as it did at the beginning of the construction on Trellick, portended trouble ahead. The site had been slum terrace housing before the GLC began Cheltenham Estate and the new site was never properly managed. The GLC did not provide security or access to the staircases, elevators and other public areas with the result that the project was vandalized even before the building was opened. Trellick was regularly featured in the tabloids as “The Tower of Terror”, and there were stories of women being raped in the elevators, children attacked by drug addicts, and homeless squatters setting fire to empty flats. The underground garages were especially dangerous. Just before Christmas in 1972, vandals opened a fire hydrant on the 12th floor landing releasing thousands of gallons of water into the lift shafts and all heat and electricity was out for several days.

The building was refurbished in the 1990’s and under new management the use of closed circuit TV, more security, and a concierge system, living conditions have improved. Few dwellings come up for sale, and residents generally like the large well-lighted flats, and spectacular views. Much of the 1970’s critique of high-rise modernist housing still apply at Trellick, problems with supervising children, the scary balconies, the harshness of the public spaces, the problems with parking and so on. As an exercise in the urban planning of a late CIAM ensemble, Trellick remains a shockingly tall intrusion built on an island of modernist blocks inserted into a difficult site with little formal or physical connection to the surrounding neighborhood. The preoccupation with the tower lends some credence to the Villa Radieuse concept of building in a park although there is not much of the park in the densely packed 11-acre site. The scene from the tower maisonettes, however, is incredible, an elevated aerial view across the vast urban landscape of London.

Trellick may have been the inspiration for the novel, High-Rise, written in 1975 by the English science fiction writer J.G. Ballard. The last of a trilogy of books (Crash, 1973, Concrete Island, 1974) exploring common dystopian themes about the impact of modern technology on the human physic, High-Rise is a bleak apocalyptic tale about the social and physical disintegration of a community of 2000 people living in a 40-story apartment tower in London. Much of the description of the tower in Ballard’s novel seem to have been derived directly from Trellick, the extended height, the facades and balconies, the articulated stairs and elevators, and the general Brutalist quality of the” concrete landscape”. Ballard’s description of the tower as “an architecture built for war” certainly seems apropos vis-à-vis the Brutalist quality of the complex.

By the time High-Rise was published, there was already heightened public antagonism towards the typical modernist social housing development of the 1960’s and an accompanying fear of high rise buildings in general. Incidents like the explosion in the Rowan Point tower in 1972, and the release of disaster films like The Towering Inferno (1974), a story about a fire in a 102-story office tower, and the earlier demolition of the Pruitt Igoe slabs in St. Louis in 1972, all contributed to a growing popular rejection of high rise-housing types.

While other earlier examples of GLC 1960’s housing estates may also have provided examples of dystopian scenes (Brandon Estate, for example, a group of 5, 17-story towers), none were as tall or quite so starkly modernist as Trellick. The deterioration of Ballard’s’ tower as the tenants slip into a state of complete anarchy and start eating each other’s dogs (and eventually each other), and most of the other problems that characterized Terllick’s early years are described here: the social stratification related to the location of one's apartment, problems with the elevators and stairs, noise, objects thrown from the balconies, muggings and assaults, fires, and the overwhelming lack of security. Like Goldfinger at Trellick, the architect who designed High-Rise, also lives in the building, there ostensibly to promote the bourgeoisie imagery of the place. While Ballard uses the high-rise building and its occupants as a metaphor for the problems of culture in general, and of man becoming the victim of the technology he creates, an embedded theme is the destructive, alienating qualities of modern architecture and especially high-rise housing.

Architect's Journal, 19/1/73, pp. 21-9

Architect's Journal, 23/11/87, pp. 28-9

Dunnett, James, Architect's Journal, Nov. 20, 1997, pp. 32-8

Dunnett, James, Ernö Goldfinger: Works, London Architectural Association, 1983

Jones, Edward, & Christopher Woodward, , Van Nostrand Reinhold, N. Y., 1983, pp. 74Architect's Journal, Nov. 20, 1997, pp. 32-8

Warburton, Nigel, Ernö Goldfinger: The Life of An Architect, Routledge, London, 2003

Trellick Tower

Trellick Tower

5 Golborne Road

London W10 5PL

Ernö Goldfinger 1967-1972

Trellick Tower is one of London's landmark attempts at high-rise residential living, still thriving almost entirely as social housing but with about one tenth of the apartments now privately owned and attracting fashionable prices and decor.

Its complex facade reflects an efficient arrangement of apartments in which corridors are needed only on every third floor, with stairs up or down to a mix of flats and duplexes. This idea, and the purity of the geometry behind it, draws strongly on Le Corbusier's Unité d'habitation in Marseille, of which Trellick is a somewhat diluted but higher-rise variant.

Goldfinger saw his role very much as an artist, bringing a view of the social future as well as the functional present:

Whenever space is enclosed a spatial sensation will automatically result for persons who happen to be within it... it is the artist who comprehends the social requirements of his time and is able to integrate the technical potentialities in order to shape the spaces of the future.

Ernö Goldfinger 1942

Part of Trellick's distinctive profile comes from the boiler house cantilevered out above the lifts, adding personality to an overtly brutalist concrete lift tower. The oil-fired boilers here to provide central heating for all the apartments. Problems with this system, compounded by the 1973 oil crisis the year after the building opened, mean that the boiler house was almost immediately redundant. Apartments are now heated with electric storage heaters, and the futuristic boiler house lies empty. (The local council refused to accept an offer for it as a private penthouse apartment.)

Simon Glynn, 2003

The Compact City - The EU's vision for the future - the lessons to be learnt from the 1960s high density development

Source: http://www.thesteelvalleyproject.info/green/Places/residential/high-rise.htm

Changing styles of housing area design 1970s to 1990s

We can now see from an extensive body of research that the missing concept for the planners and designers of the time was that the outdoor spaces needed to provide local people not only with facilities, but also with a range of experiences, that is, to provide satisfactory settings for daily life in the home environment. (Summary of relevant research: Beer,1990 and 2000.) The author fears that if the buildings that are going up at present are a guide, this concept is still missed by too many of today's designers as well.

By the end of the 1960s and into the early 1970s, at a time when the first research evidence of the failure of many high density housing designs was being published, a new issue came to dominate the site layout and detailed design ideas of architects, landscape architects and planners and determined the decision-making behaviour of many of them: an increasing awareness of the need to integrate natural habitats into housing areas. This concept diverted attention from the much more complex problems of the role of the external spaces being thrown up by sociological studies. Instead of addressing the problems of how to design the outdoor spaces holistically in relation to the full range of experiential needs of local people, these designers focused attention on one particular aspect of the human experience - contact with nature - a vitally important element of an individual's experience of daily life, although not the only one.

In the Netherlands and Scandinavia the 'nature in the city' concept grew in strength from the late 1960s to the 1980s. It had a major impact on the way the external spaces of high density housing areas were designed and how the landscape that resulted was managed. Nature was integrated into high density, high-rise schemes such as the Bijlmer, Amsterdam and Beethovenlaan, Delft -ARB check places and get photos. That this approach also failed to produce residential environments which the inhabitants found satisfactory, we can now see was unsurprising: - the planners and designers still neglected to cater for the ordinary every day human experiences - they did not ask the question 'what is it like to live in this house/block and move to it and from it?'

By the late 1970s the fashion for high density, high-rise housing schemes with large areas of open and greenspace was over. Planners' and designers' efforts were diverted into low-rise, middle density housing. Family housing with gardens became the vogue in western Europe. The problem now became one of keeping any open space at all in the new developments - many were produced by private developers who were loathe to take on the added burden of providing open space accessible to the general public. The result of this changing agenda was that the problems of the high-rise estates were forgotten; they are indeed very different from those associated with the sea of low-rise, middle density housing which became the common form of housing until very recent times.

Source: http://www.thesteelvalleyproject.info/green/Places/residential/high-rise.htm

The prevalent ideas about the role of Greenspace in housing during the 1960s

Demand for housing was very high during the 1960s. Governments throughout Europe became convinced that high density housing, of the type described from the 1920s to the 1950s by le Corbusier and other architects as suitable for the 'masses', was the answer to providing new housing quickly. Many of the developments that resulted (in the main large slab blocks, with some tower blocks interspersed with 3/4 storey housing for the slightly better off) were initially liked by their new inhabitants. However almost without exception, the schemes became associated with a range of social problems over time. This led in many instances to a mass exodus of the more stable families and the better off to what were regarded by them as more appropriate surroundings for their residential life.

The high-rise housing of the 1960s differs greatly from that being built today - in particular it tends to be associated with wide open spaces between the buildings. During the 1960s greenspace was recognised as a valuable attribute of any area of a city and government-approved standards of provision for different types of greenspace were a major component of the planning process (for example, the British new towns). However, greenspace was only understood by planners and designers in two ways. It was either:

- the spaces left over after buildings were erected or infrastructure laid out - the Dutch even today call it 'kijkgroen' (green to look at), or

- those areas of land supporting specific active recreational activities.

Those involved as greenspace designers at that time saw their role as making the area 'look good' and the architects, who for want of any other guidance reproduced the designs of the le Corbusier school (albeit in a modified form), reproduced the 'parkland' settings shown in the architects' drawings of the 1920s to 1950s. The present 'parkway' road systems found in many of the larger 1960s estates all over Europe come directly from such images. The designers of such large=scale estates (for example, Overvecht, The Netherlands, houses over 30,000 people) were indeed spectacularly successful in creating the 'Housing in a sea of parkland' image. The only problem was that this design style was not suitable as a support for ordinary daily human existence. (Parkland as an original design style was invented as a setting for large buildings, but only for a single large building inhabited by a few of the very rich, their servants and hangers on, for people who led a very 'controlled' social life. It was never intended as a style which could create a setting for the daily home life of 30,000 people with all their disparate social needs.) It was a landscape style which saw people passing through or looking down on greenspace, not using it as 'their place', not enjoying being in it.

This limited understanding of the role of open spaces (the green and the hard-surfaced) in housing developments, which existed throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, was exacerbated in its social impacts by being linked to stringent governmental guidance in the UK at least on the quantity of open space to be provided per thousand new inhabitants. The prevalent idea at the time about appropriate design style linked to these space standards does much to explain the vast hectares of open space in such schemes.

The end result has been that much of this space is hardly used and is often regarded as alienating and sometimes even frightening by the local inhabitants. Recent user surveys have shown clearly that those same inhabitants tend not to want to lose any of the open unbuilt land adjacent to their homes - they value its presence and potential 'specialness' highly. What they do want though is that the space should work better to support what they want to be able to do outside and near their dwellings (see Overvecht case study - summary of local people's identification of key issues in the regeneration of the external areas of the estate).

Research since the 1960s has shown that local people find the 'outdoors' of such housing areas as unsatisfactory settings for their daily life (Clare Cooper Marcus and Wendy Sarkissian, 1987). Local greenspace can be seen in the research to influence strongly:

- how local inhabitants experience their home environment

- how satisfied they are with it as a place in which to live.

Source: http://www.thesteelvalleyproject.info/green/Places/residential/high-rise.htm

Some reasons why greenspace in the high density housing estates of the 1960s and 1970s remain a problem

As we move into a time when the building of medium to high density housing is once more fashionable, it would seem essential that we learn from past mistakes. Yet on all too many recent high-rise schemes in the UK, we see a repetition of past patterns in relation to how the external environment is considered. Evidence as far back as the 1970s from post occupancy evaluations of such estates showed that the inhabitants were often initially delighted with their new accommodation just as today, but that within a short period the external environment became perceived as a problem, which led to reduced levels of satisfaction and in many cases the ultimate rejection of these environments as suitable settings for modern residential life (DOE,1972). That the post occupancy research continues to be ignored by the designers of social housing remains a cause for concern.

In many schemes in the UK today it appears that the developers' solution to this problem is to have no 'external spaces' within the boundaries of their site! Where children will play, or older people can sit in the sun as they wait for friends, and where they will see greenery, are forgotten factors. It could be argued that such issues are the city's responsibility, but in the present financial regime they have no spare money to buy, design or look after the land required if such 'places' are to be provided. The increasing evidence of a link between health and greenspace (Grahn, 2003) alone should cause a rethink of this situation - the cost to society of sick, older people continues to rise, yet we know that daily exercise increases health levels and we know that looking out at greenspaces has a positive effect on the human mind and through that on the body (Ulrich, 1999).

There is an urgent need to rethink the role of this local open space in high density housing in general because of the EU's guidance on the need to develop all expanding cities as the 'Compact City'. If we cannot get the older high density schemes to work properly as a satisfactory setting for daily life, then what hope is there in the new developments now on the drawing board and being built at similar or greater densities?

In the main there is still a lack of proper consideration being given to the experiential aspects of the external environment around the home.

Source: http://www.thesteelvalleyproject.info/green/Places/residential/high-rise.htm

Absorbing Venice. High Density Low Rise Housing by Louis Sauer

I immediately thought of Louis when I was asked to give a paper at the ILAUD Residential Course in Venice. I thought of the student-architects coming to Venice from all over the world, forty years after that CIAM Summer Course and the same age as Sauer was then. ILAUD certainly owes something to the pioneering experience of the CIAM Summer Course and not just because of the presence of De Carlo, who also organised the 1956 one. A lot of things have changed since then. Not the fact that architects need to study, debate and exchange ideas with citizens, administrators and builders, but that their job, ultimately, is to get things done: deft, intelligent designs that slice through bureaucracy and tiredness like a rapier. So, the CIAM Summer School at Venice in the '50s (the themes of a triennial of that experience included the Tronchetto and the Biennale Gardens) and ILAUD forty years later with the island of Sant'Elena: think of the continuities and differences, the reflections and observations we might continue to weave together. A second reason for the choice was that the intellectual figure of Sauer and his achievement, though so close to ILAUD and in many ways an organic part of it, deserve to be presented directly, even if this risks being less popular. (Gehry, Eisenman or even Terragni have much greater appeal). Somehow nowadays it's unfashionable to arrive at architecture from the difficult field of housing. You come up against the old theme of ëexceptional' architecture and ëeveryday' architecture: but isn't that a false problem? But the decisive reason behind my choice was different. I thought about the evolution of Louis's work and the many discussions together about Venice. I reflected that in the experiences of the student-architects here in 1997 there will be two phases. The first is the ëcontact', the four weeks passed physically in the city with the challenge of a project to tackle; the second will be the process of ëincubation'. A personal reflection, lasting I suppose all one's life, where the seed of Venetian architecture will continue to grow. At least this is what happened to Louis Sauer. Using his work as an instrument, I want, in short, to plant the seed of this city even deeper. It is sure to grow.

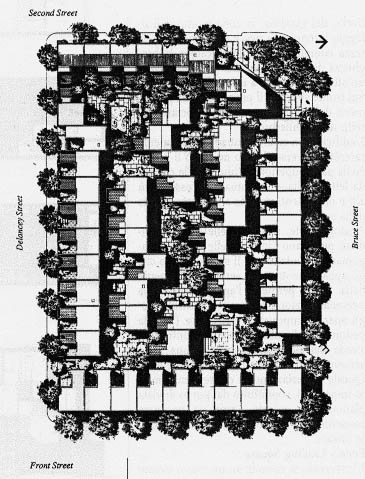

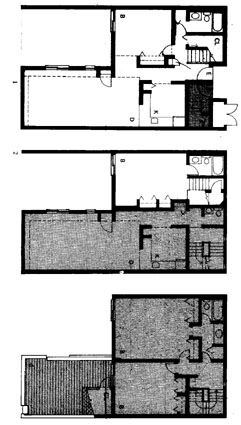

Penn's Landing square, Philadelphia

While Sauer was assimilating a conception of the architect's work rooted in the functionalist tradition (hence practical adherence to a theme, an attempt to influence society through architectural design, a scientific conception of the gradual accumulation of understanding as opposed to the academic and formalist concept of the single splendid gesture), he also had an idea of urban space that was opposed to the functionalist concept. He rejected the separation of building from ground (with isolated volumes suspended on an even level surface, continuous and laid out as a garden, of the Charter of Athens), replacing it with the idea of an interwoven fabric. The ground is no longer a surface on which to rest volumes but a whole to be designed carefully as a compact whole, in which spaces, streets, buildings, gardens and paved areas all interact. His designs are governed by a homogeneous grid, but the grid empties, opens and closes to create a continuum of relationships between the various parts and evoke the small pathways, sudden surprises, the atmosphere and values of the historic city, but applying new techniques and modern standards. The second idea is closely bound up with the first. After an emergency phase, with internationalized problems and standardized solutions, the specific context in which each single architectural work has to be created enters forcefully into a project. ëContext' is a necessarily ambiguous term, because it indicates the specific morphology of the site but also its historic and cultural stratifications. The consequence of this is decisive: designing no longer means laying down ëmodels' that can be inserted in a variety of different contexts (as the great masters long thought), but the study of ëmethods', i.e. techniques of design that are flexible and adaptable. From model to method means using the scientific approach of functionalism at a much higher and more complex level: to aim at diversified solutions and their flexibility, to leave the architecture free in planimetric and volumetric compositions, to adhere to the programs and interpretations that everyone has of the context. Now Venice may well have offered a source of forms, styles, colours, atmosphere, materials and so forth, and also a help to understanding, like few other cities in the world, precisely these two key facts. How urban space can be based on a continuous fabric (though articulated in a variety of ways) and how architecture, especially housing, can concretely create this fabric, based on a continuous series of variations within a set of guidelines. Like, for example, low rise/high density.

Low-rise high-density housing

In many ways Venice is the source of the system of development called ëlow-rise high-density': a way of conceiving urban space that overturns the Functionalist logic of separating buildings from the ground, being based on continuity, articulation, territoriality. This strategy, present in the experience of some of the members of Team X, was used by the Swiss architects of Atelier 5, and other pioneers like Darbourne & Deave or Neave Brown in Britain: but some of its most convincing and mature achievements are found in the works of Sauer. They range from the creation of sections of new towns to low-cost housing in extensions of the city, to particularly delicate projects inserted in the fabric of existing cities, like the historic complex at Society Hill. Low-rise high-density housing is based ultimately on four principles: - to reach adequate real-estate densities suited to an urban setting (350-550 inhabitants per hectare) through blocks not more than four storeys high; - to provide each home-unit with a strong sense of individuality with the clear identification of separate elements of access, as far as possible directly from ground level; - to eliminate spaces without a precise territorial connotation, in particular to privatize most of the outside spaces by relating them directly to home-units; - instead of keeping housing blocks, streets and spaces separate, to create continuity of the constructions by a system of ëbuilt fabric', governed by a grid and achieved by a system of ëoverlapping home-units'.

Penn's Landing square, Philadelphia

Penn's Landing Square, the most significant project at Society Hill and the only one we can examine here, was designed through a succession of laborious drafts. In the final draft Sauer passed from 25 home-units per acre (about 250 inhabitants per hectare) to 50 home-units per acre, so with a real-estate density twice the earlier scheme. The project is based on continuity of the outer perimeter to defend spatial variation in the internal pedestrian and public spaces; the insertion of underground parking in the lower part of the block; the location of town houses along two of the outer fronts; but the basic instrument used to create the project (above all the challenge of achieving high density within the limit of three-storeys), was the invention of a ëhousing package' of superimposed units.There are five fundamental ideas underlying this solution (they are at once technical and distributive, planimetric and formal): - The package is based on two structural bays of 4.20 m to form modules of about 8.80 m arranged along the grid, which decides the size of the project in constructional and spatial terms. The linear aggregation permits both the alignment of the home-units as a continuous row on one of the outer fronts as well as enabling them to be staggered independently from each other inside the perimeter. - Within the homes, the different surface areas of the units (from about 80 to 135 sq m) is achieved by extending into the space of the adjoining structural bay, where necessary, and so forming either units on one floor only, or on two floors in two bays, or in one bay on one floor and two on the floor above. The flexibility in the size of the units also stems from the decision to locate the staircase along one front orthogonally positioned in relation to a bay. The result is that the units are organised through a division into a service belt (stairs, entrance, bathroom) and a served belt (living-room, dining-room and bedrooms). - The service-served organisation is also functional in terms of density. The served front of one row faces onto the service front of another. This enables the fronts of the parallel rows of housing to be brought much closer together, ensuring the high densities required, but avoids an 'introverted' building. Moreover the served front is oriented south to optimise the exposition. - The actual functionality of the system is guaranteed by its L-shaped layout which gives an extra front compared with rectangular layouts. On the ground floor, where the problem of light is greater, the served front opens onto the inside of the 'L' towards the private garden. On the upper floors the built masses are stepped back so that part of the surface area becomes a terrace. In this way, instead of being based on the typical functionalist approach which has a standard cell aggregated along a layout to form a model building (itself multiplied x times to create the neighbourhood), the project is based on a triad consisting of cell-housing package-building. The package contains within itself the home-units and system of distribution, and the single packages are not constructed by a system of distribution on a higher scale. Hence it is the various aggregations and combinations of the housing package that enable the complex to be organised to meet the requirementrs and characteristics of spaces, internal planimetric links and external relations with the city.

Penn's Landing square, Philadelphia

Form and context

The housing package makes it possible to achieve an articulation of internal spaces based on the contraction and dilation of interiors in a sequence of contrasts of light and shade, solids and voids, public and private ambits. The source of these alternations was Sauer's love for the way the little calle leads to a campo, and the campo in turn to a calle, a fondamenta or a smaller campo. But in this project, like all Sauer's designs, there is a big difference between interior and exterior. Here the outer perimeter is continuous and rigid and at first could be seen as a great wall enclosing the project. Yet if you look at it at more closely you discover important variations in this wall. The small residential scale of the existing houses on one side is expressed by identiyfing the individual home units, rhythmically marked off by the volumes of the terraces running along the street front. By contrast a second front appears as a surface only cut into by windows, creating the effect of an urban screen for the buildings terminating the street and an introduction to the corner volumes of the main entrance. On the other two sides, to respond to the distant view from across the Delaware River, a strong, compact screen is created by increasing the height of the front (inclining the roof inwards) and grouping the windows together. The integrity of the surface facing the river is achieved by the compact band running along the top, while the attachment at ground level is rhythmically marked by the apertures containing the entrances and enriching the perception of viewers on the sidewalk. Penn's Landing Square is an important project for understanding how to design in a built city, how to replace derelict housing and redevelop industrial sites or docklands, like Society Hill in the past and some parts of Venice now. Of course this is an exclusively residential project, while today we tend to seek a mix of functions so as to revive inner cities. Here the underlying concept is of a fabric based on a grid and the way it is filled or emptied, while in Venice the approach may be as well to start from the possibility of working with forms, i.e. through morphologies that are dynamic right form the start. The most important recent projects at Venice, one on the Giudecca and and the other on Mazzorbo, indicate precisely these two different approaches. Some details of Sauer's design may not convince everybody, but I feel whoever believes that the road of architectural research must pass through housing will find this project absolutely essential. The fact that, at least in the architect's aspirations, it has a lot of Venice in it is one more reason to present it here at ILAUD 1997.

Source: http://www.arc1.uniroma1.it/saggio/Libri/Sauer/SauerIlaud.html

High Density Housing

Note: Some of the information in this post is taken from an exhibition I visited a few weeks ago at the Tate Modern called Global Cities. The exhibition examined urban and social issues in ten large cities around the world and was full of fascinating facts.

According to the United Nations (UN), 50% of the world’s population now live in cities compared to just 10% over a century ago. By 2050, this figure is expected to rise to 75%.

As more people flock to cities, so pressure on housing grows. In the UK, London’s population is on the rise - although growth is modest compared to other cities. According to the UN, London ranks 360th in the list of fastest-growing cities in the world.

Planning authorities in London have decided to contain the growth of London’s population within its existing boundaries rather than let the city expand. What does this means for housing in the Capital? A common perception is that as city populations grow, higher-density housing must take the form of high-rise tower blocks.

Many people in London probably already feel the city is overcrowded, but London is actually a relatively low-rise, low-density city. Almost half (46%) of Greater London consists of open and recreational space. In Los Angeles, only 10% of the city is allocated to green open spaces and in Tokyo, less than 5%.

High-rise living brings with it a set of preconceptions and problems. Many of us aspire to own a detached house and garden even though this is unrealistic - there simply isn’t the land available.

But high-density living doesn’t have to mean high-rise towers - it could mean relatively low-rise blocks of five or six storeys with their own communal space. Communal space can never match the appeal of a garden: one reason why apartment blocks are seen as unattractive to families who want a place for their children to play.

Ground floor flats can be designed to include private outdoor space (and a private entrance), thus mitigating one of the perceived disadvantages of apartment living. Top floor flats too, could have a roof terrace. Flats can also be made into duplex units (i.e. spread over two floors), giving a more house-like feel. But there are still other issues to contend with.

For example, high rise blocks are also associated with high service charges. A lift becomes a necessity once a block has more than four or five floors but that also adds to the maintenance cost of the building. However, even if we limit the number of floors to four and dispense with a lift, a family with young children are unlikely to want a top floor flat (even one with a roof terrace) if they have to climb four flights of stairs.

Shared communal spaces can also present problems. Residents of a block may all have different ideas about how they would like to use the space. A family may want their young children to play. Some residents may want to invite friends for socialising, while others may simply want a quiet outdoor area to relax. With all these competing wants, residents can easily become unhappy with how communal areas are used if it disturbs their own privacy or peace and quiet.

It’s important that all residents of a flat have some private outdoor space, which for most will mean a balcony. Balconies should ideally be hidden from view from neighbouring flats so residents feel they are not being looked upon from above or the side. When balconies jut out in plain view of everyone, they are rarely used for anything but hanging the laundry out (which is still an important and useful function).

Which brings us to our next concern: noise from neighbours and the potential lack of privacy. There’s no reason why new build flats can’t be completely soundproofed. Soundproofing is not rocket science, neither is the cost prohibitive if considered thoroughly at the design stage. I’m fairly certain that touting the soundproof qualities of a flat would be a strong selling point that many potential buyers would find reassuring.

Of course, as soon as you open a window, noise enters from many different directions. Depending on the proximity of neighbouring windows, you may even hear your neighbour’s music/TV/conversations if their windows are open too. This can be minimised to some extent by sufficient spacing of adjacent windows in neighbouring flats and by designing the layout of apartment blocks such that the living room or area of one flat is not adjacent to the living room of a neighbouring flat. Realistically, we have to expect some noise when living in high-density, urban environments, but thoughtless or inconsiderate design can exacerbate noise problems rather than reduce them.

There’s another issue to contend with: just how high should a high-rise be? Many people don’t consider a four or five storey block of flats as high-rise. Perhaps a better term to use is high-density. The word density in relation to tower blocks conjures up images of cramped, overcrowded conditions. But there’s nothing to preclude spacious apartments with natural light and natural ventilation in a high-rise block - it all comes down to the initial design.

In his book, A Pattern Language, architect Christopher Alexander argues that buildings designed for living in, should be limited to a maximum of four storeys.

“In any urban area, no matter how dense, keep the majority of buildings four storeys high or less. It is possible that certain buildings should exceed this limit, but they should never be buildings for human habitation.”

Alexander goes on to argue that high rise living can be socially isolating:

“High rise living takes people away from the ground and away from the casual, everyday society that occurs on the sidewalks and streets and on the grounds and porches. It leaves them alone in their apartments. The decision to go out for some public life becomes formal and awkward; and unless there is some specific task which brings people out in the world, the tendency is to stay home, alone.”

The arguments sound quite convincing, but I’m not sure I agree entirely with the four storey limit. I think there are also cultural and social factors that contribute to whether high-rise living in tall tower blocks are a success or a failure.

In Britain, we tend to associate high-rise living with run-down council tower blocks and it’s easier to recall failures in high-rise housing than it is to think of more positive examples. Tower blocks comprise a very small proportion of Britain’s total housing stock which means that the majority of us are not accustomed to high-rise living. This in itself has important implications for the development of future high-density towers.

The quality of high-density housing varies enormously across the globe. In some countries like Hong Kong and Singapore, high-rise living is a necessity. We can learn a lot about high-density housing, not just from our own success and failures, but the experience of others too.

Source: http://homesdesign.wordpress.com/2007/09/09/high-density-housing/